AN INSPECTOR CALLS

An Essay Writing Guide for GCSE (9-1)

So you now know the play – but how do you structure your essay?

This clean & simple new guide from Accolade Press will walk you through how to plan and structure essay responses to questions on J. B. Priestley's An Inspector Calls. By working through nine mock questions, these detailed essay plans will show you how to go about building a theme based answer – while the accompanying notes will illustrate not only how to masterfully structure your response, but also how to ensure all AQA's Assessment Objectives are being satisfied.

R.P. Davis has a First Class degree in English Literature from UCL, and a Masters in Literature from Cambridge University. Aside from teaching GCSE English (which he's done for nearly a decade now), he has also written a string of bestselling thriller novels.

Online shopping options:

Alternatively, you can purchase and download an electronically delivered PDF directly from us here.

Sample from the Guide

Foreword

In your GCSE English Literature exam, you will be presented with two questions on J. B. Priestley’s An Inspector Calls, and you will then be asked to pick just one to answer. Of course, once you’ve picked the question you prefer, there are many methods you might use to tackle it. However, there is one particular technique which, due to its sophistication, most readily allows students to unlock the highest marks: namely, the thematic method.

To be clear, this study guide is not intended to walk you through the play act-by-act and sequence-by-sequence: there are many great guides out there that do just that. No, this guide, by sifting through a series of mock exam questions, will demonstrate how to organise a response thematically and thus write a stellar essay: a skill we believe no other study guide adequately covers!

I have encountered students who have structured their essays all sorts of ways: some who’ll write about the play chronologically, others who’ll give each character their own paragraph. The method I’m advocating, on the other hand, involves picking out three to four themes that will allow you to holistically answer the question: these three to four themes will become the three to four content paragraphs of your essay, cushioned between a brief introduction and conclusion. Ideally, these themes will follow from one to the next to create a flowing argument. Within each of these thematic paragraphs, you can then ensure you are jumping through the mark scheme’s hoops.

1) Priestley’s profile as rendered in Ivegate Arch, Bradford. Copyright © Tim Green

So to break things down further, each thematic paragraph will include various point-scoring components. In each paragraph, you will include quotes from the play (yes, that means you’ll have to have some committed to memory!), offer analyses of these quotes, then discuss how the specific language techniques you have identified illustrate the theme you’re discussing. And in most every paragraph, you will comment on the era in which the play was written and how that helps to understand the chosen theme.

Don’t worry if this all feels daunting. Throughout this guide, I will be illustrating in great detail – by means of examples – how to build an essay of this kind.

The beauty of the thematic approach is that, once you have your themes, you suddenly have a direction and a trajectory, and this makes essay writing a whole lot easier. However, it must also be noted that selecting themes in the first place is something students often find tricky. I have come across many candidates who understand the play inside out; but when they are presented with questions under exam conditions, and the pressure kicks in, they find it tough to break their response down into themes. The fact of the matter is: the process is a creative one and the best themes require a bit of imagination.

In this guide, I shall take nine different exam-style questions, and shall put together a plan for each – a plan that illustrates in detail how we will be satisfying the mark scheme’s criteria. Please do keep in mind that, when operating under timed conditions, your plans will necessarily be less detailed than those that appear in this volume.

2) A statue depicting Priestley at his typewriter. Copyright © Tim Green

Now, you might be asking whether three or four themes is best. The truth is, you should do whatever you feel most comfortable with: the examiner is looking for an original, creative answer, and not sitting there counting the themes. So if you think you are quick enough to cover four, then great. However, if you would rather do three to make sure you do each theme justice, that’s also fine. I sometimes suggest that my student pick four themes, but make the fourth one smaller – sort of like an afterthought, or an observation that turns things on their head. That way, if they feel they won’t have time to explore this fourth theme in its own right, they can always give it a quick mention in the conclusion instead.

* * *

Before I move forward in earnest, I believe it to be worthwhile to run through the four Assessment Objectives the exam board want you to cover in your response – if only to demonstrate how effective the thematic response can be. I would argue that the first Assessment Objective (AO1) – the one that wants candidates to ‘read, understand and respond to texts’ and which is worth 12 of the total 30 marks up for grabs – will be wholly satisfied by selecting strong themes, then fleshing them out with quotes. Indeed, when it comes to identifying the top-scoring candidates for AO1, the mark scheme explicitly tells examiners to look for a ‘critical, exploratory, conceptualised response’ that makes ‘judicious use of precise references’ – the word ‘concept’ is a synonym of theme, and ‘judicious references’ simply refers to quotes that appropriately support the theme you’ve chosen.

The second Assessment Objective (AO2) – which is also responsible for 12 marks – asks students to ‘analyse the language, form and structure used by a writer to create meanings and effects, using relevant subject terminology where appropriate.’ As noted, you will already be quoting from the play as you back up your themes, and it is a natural progression to then analyse the language techniques used. In fact, this is far more effective than simply observing language techniques (metaphor here, alliteration there), because by discussing how the language techniques relate to and shape the theme, you will also be demonstrating how the writer ‘create[s] meanings and effects.’

Now, in my experience, language analysis is the most important element of AO2 – perhaps 8 of the 12 marks will go towards language analysis. You will also notice, however, that AO2 asks students to comment on ‘form and structure.’ Again, the thematic approach has your back – because though simply jamming in a point on form or structure will feel jarring, when you bring these points up while discussing a theme, as a means to further a thematic argument, you will again organically be discussing the way it ‘create[s] meanings and effects.’

AO3 requires you to ‘show understanding of the relationships between texts and the contexts in which they were written’ and is responsible for a more modest 6 marks in total. These are easy enough to weave into a thematic argument; indeed, the theme gives the student a chance to bring up context in a relevant and fitting way. After all, you don’t want it to look like you’ve just shoehorned a contextual factoid into the mix.

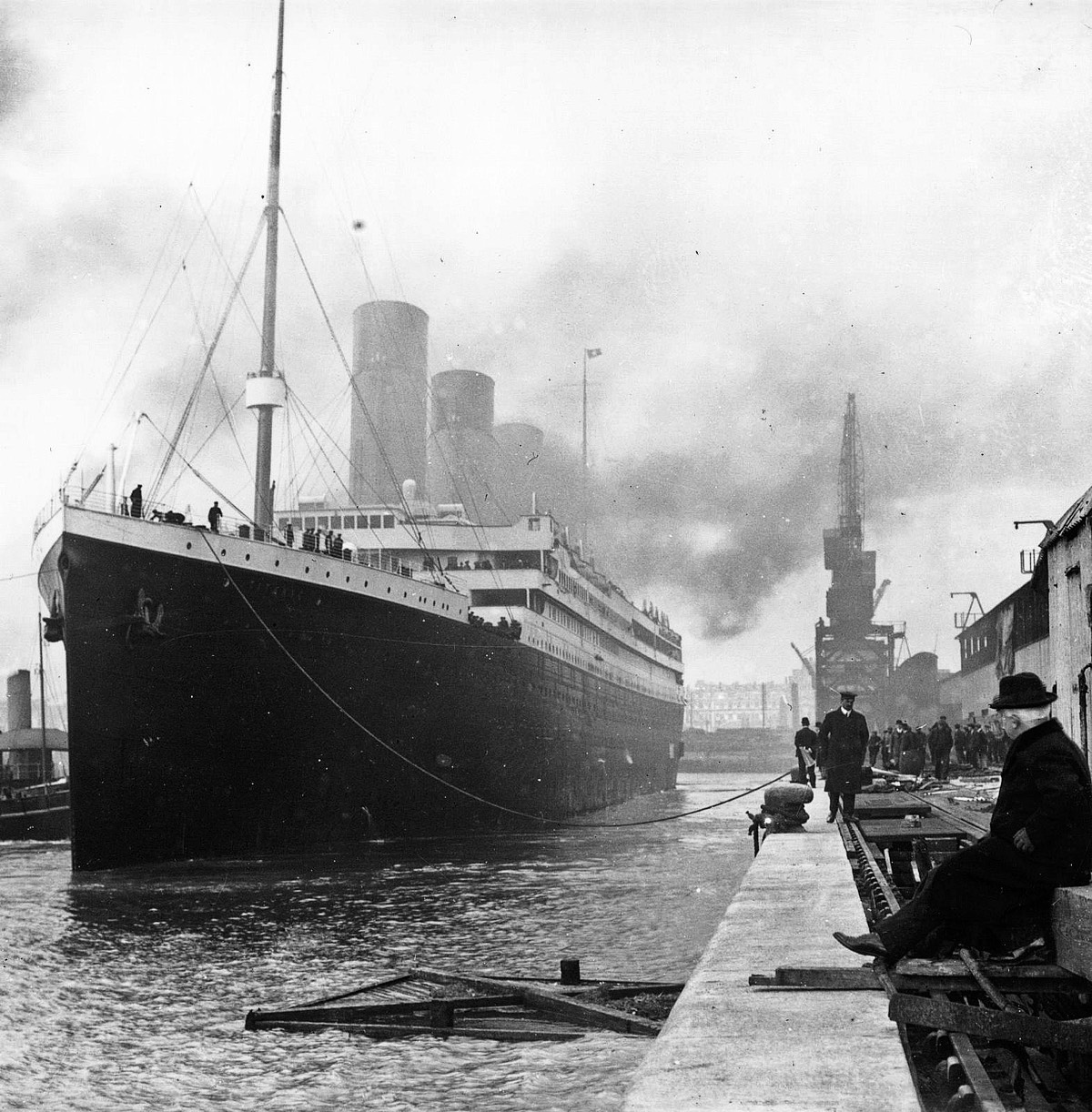

3) A photo of the Titanic in Southhampton in April 1912, prior to its disastrous maiden voyage. Birling’s comments about the Titanic are key to understanding his character.

Finally, you have AO4 – known also as “spelling and grammar.” There are four marks up for grabs here. Truth be told, this guide is not geared towards AO4. My advice? Make sure you are reading plenty of books and articles, because the more you read, the better your spelling and grammar will be. Also, before the exam, perhaps make a list of words you struggle to spell but often find yourself using in essays, and commit them to memory.

* * *

My hope is that this book, by demonstrating how to select relevant themes, will help you feel more confident in doing so yourself. I believe it is also worth mentioning that the themes I have picked out are by no means definitive. Asked the very same question, someone else may pick out different themes, and write an answer that is just as good (if not better!). Obviously the exam is not likely to be fun – my memory of them is pretty much the exact opposite. But still, this is one of the very few chances that you will get at GCSE level to actually be creative. And to my mind at least, that was always more enjoyable – if enjoyable is the right word – than simply demonstrating that I had memorised loads of facts.

Essay Plan One

How does Priestley explore responsibility in An Inspector Calls?

Introduction

I often suggest kicking off the introduction with a piece of historical or literary context, because this ensures you are scoring AO3 marks (marks that too often get neglected!) right off the bat. It’s then a good idea to quickly touch on the themes you are planning to discuss, since this will alert the examiner to the fact that AO1 is also front and centre in your mind.

“Given that in the wake of WW2 the world found itself cleaved between two competing ideologies – an Anglo-American capitalism and Russian style communism – it is unsurprising that Priestley’s 1945 play found itself preoccupied with these duelling ideologies.1 Indeed, a key discrepancy between these ideologies comes under particular scrutiny: their conceptions of social responsibility. If Birling is the voice of the self-interested capitalist who abrogates all social responsibilities, Goole is Priestley’s mouthpiece for a socialist dogma that insists social responsibilities be acknowledged: a dogma that sways the younger Birlings yet not the older contingent.2”

Theme/Paragraph One: Priestley explores responsibility at the societal level: Birling is the voice of a capitalist laissez-faire attitude towards social responsibility, whereas Goole backs a socialist model of heightened responsibility.3 By casting Goole as the protagonist, and Birling as antagonist, the play tacitly suggests the socialist model is morally superior.

• In the play’s opening act, Priestley has Birling sing the praises of the capitalist mentality of minimal social responsibility: in an after-dinner speech, Birling asserts that ‘a man has to make his own way – has to look after himself,’ and dismisses the idea that ‘everybody has to look after everybody else’ as ‘nonsense.’ Birling’s vitriol for the socialist model is perhaps best conveyed in a simile likening it to ‘bees in a hive’ – an image which, by equating the mindset of socialists to that of insects, suggests it to be intellectually regressive and dehumanising. However, Priestley seeks to subvert Birling’s attitude from the off. Exploiting the fact that the play is set in 1912, Priestley places comments steeped in dramatic irony in Birling’s mouth: Birling dismisses the likelihood of war (‘the Germans don’t want war’) and pronounces the Titanic ‘unsinkable.’4 The self-evident foolishness of these comments immediately throws his entire worldview into question. [AO1 for advancing the argument with a judiciously selected quote; AO2 for the close analysis of the language; AO3 for placing the text in historical context].

• Of course, Priestley deconstructs Birling’s worldview more emphatically through the character of Goole. The timing of Goole’s arrival (almost immediately after Birling’s pronouncements) instantly hint that he will offer a counterpoint, and the mere fact he bothers chastising Birling for firing unionised workers, or Sheila for having a shop attendant sacked, points to his socialist bona fides: these are not legal transgressions an inspector would ordinarily follow up, but rather social ones.5 However, the clearest articulation of his ideology of heightened social responsibility comes in the staccato sentences just prior to his departure in Act 3: ‘We are members of one body. We are responsible for each other.’ [AO1 for advancing the argument with a judiciously selected quote; AO2 for discussing how form and structure shapes meaning].

• The arc and staging of the story – in which the unflappable Goole, who is repeatedly described as ‘taking charge,’ exposes Birling’s blustering hypocrisies – ensures that Goole’s view on social responsibility, the one that the socialist-minded Priestley in fact favoured, is the one the audience is encouraged to favour, too. [AO1 for advancing the argument with a judiciously selected quote].

Theme/Paragraph Two: As the play unfolds, Goole is able to instil a sense of responsibility in the Birling children, yet fails to achieve the same with their parents. The play is an exploration of the degree to which people might be awakened to the ideology of social responsibility.

• As Goole turns his attentions to Sheila later in Act 1, and dredges up the occasion she had a woman (supposedly Eva Smith) sacked from her job at a clothing store, Sheila proves credulous to Goole’s idea that this incident, while perhaps not a legal transgression, had contributed to that girl’s suicide. Goole explicitly asserts that Sheila is ‘partly to blame,’ and Sheila internalises the notion: by the start of Act 2 (a heart-beat later in the play’s structure), Sheila is keenly shouldering the responsibility: ‘I know I’m to blame – and I’m desperately sorry.’ Even when Gerald, in Act 3, discovers that Goole was in fact not on the police force and there had been no woman in the infirmary, Sheila maintains a sense that they still ought to be shouldering responsibility: her sardonic response to her parents’ blame dodging – ‘So there’s nothing to be sorry for, nothing to learn’ – makes clear she thinks the exact opposite.6 [AO1 for advancing the argument with a judiciously selected quote; AO2 for the close analysis of the language and for discussing how structure shapes meaning].

• Although more reluctant to face responsibility in the first place (as symbolised by his fleeing the household in Act 2), Eric also eventually proves amenable to Goole’s philosophy of responsibility taking (as symbolised by his voluntary return). Of course, in many respects Eric’s transgressions are heftier and more legally perilous – he stole, and potentially committed rape – and thus the onus on him to shoulder responsibility is surely greater. Nevertheless, he does indeed do so, echoing Sheila’s sentiments in the play’s final sequences. [AO2 for discussing how structure shapes meaning].

• However, whereas the Birling children internalise the concept – so much so that Sheila starts advocating for this worldview almost as vehemently as Goole – Priestley presents the older Birlings as so repulsed by the idea of social responsibility that, even when faced with their historical acts of cruelty, they refuse to budge: as Mrs Birling puts it near the end of Act 3, ‘I have done no more than my duty.’ [AO1 for advancing the argument with a judiciously selected quote].

Theme/Paragraph Three: Priestley’s play explores the difference between taking responsibility and being held responsible. Although the older Birlings may refuse to take responsibility, Priestley explores how all of the Birlings, plus Gerald, are held responsible through Goole’s interrogations.

• Given that submitting to Goole’s interrogations might be considered a kind of punishment in its own right, the persistent questioning each of the dinner attendees face ensures that, even if the character in question refuses to take responsibility, they are still held responsible. Often it is Priestley’s stage directions that best reveal the distress the characters are undergoing as they take their turn under Goole’s spotlight. Even the stubborn Birling and Mrs Birling are variously described as behaving ‘angrily,’ ‘bitterly’ or ‘annoyed’ as they weather Goole’s interrogations. Gerald occupies a more equivocal position than the duelling Birling generations: he is contrite, yet does not become an evangelical adherent of Goole’s mentality.7 Nevertheless, he too is held responsible by Goole, and meets with a very real punishment: losing his fiancée. [AO1 for advancing the argument with a judiciously selected quote; AO2 for the close analysis of the language].

• Although the crimes in question are of course not analogous, this notion of holding individuals responsible – including those who may refuse to acknowledge their responsibility – was particularly pertinent in the year the play was released.8 After all, four months after the play premiered in July 1945, the Nuremberg Trials got underway: trials specifically designed to prosecute the key players in the Nazi regime, including the unrepentant among them. [AO3 for placing the text in historical context].

• However, it is not just Goole that holds the Birlings to account, but the fictional universe in which they exist, too. In what Priestley surely wishes the audience to construe as a supernatural twist, the Birlings and Gerald, after satisfying themselves that at least a portion of the night’s proceedings had been a hoax, receive a call informing them that a girl had just committed suicide and that officers are en route to quiz them.9 This suggests that their collective punishment is about to recommence – indeed, given Birling’s ‘panic-stricken’ face, one assumes it already has. [AO1 for advancing the argument with a judiciously selected quote].

• While it has previously been noted that the Birling parents are unrepentant, it is perhaps worth noting that the final stage direction describes all the Birlings and Gerald as staring ‘guiltily,’ raising the possibility that this final turn of events might have finally forced the older Birlings to acknowledge some responsibility. [AO1 for advancing the argument with a judiciously selected quote].

Conclusion

We have a very meaty essay here, so I don’t think a standalone fourth theme is necessary – and yet I do have one last idea up my sleeve: namely, that Priestley also asks the audience to consider the extent of their own responsibility. As a result, I have slipped this argument into the conclusion, thereby ensuring that I go out with a bang!

4) A statue of Priestley in his hometown of Bradford, UK. Copyright © Tim Green

“The idea of responsibility is inseparable from Priestley’s play, and bleeds into its every nook and cranny. One might even reflect how Priestley subtly uses his play to explore responsibility on the audience’s part as well. Given Goole’s systematic grilling of everyone in the room, the audience might be left with the uncomfortable feeling that they might also come under scrutiny themselves at any moment. This dynamic cunningly invites the audience to consider (and, where appropriate, take responsibility for) their own complicity in capitalism’s excesses, too.”

Footnotes

1 Capitalism and communism are hugely significant terms, but can be tricky to define. I’ll try and do so briefly.

Capitalism is a philosophy that suggests that a society should be run on the basis of the free market. Goods and services are provided by private companies, and the prices of goods and services depend solely on supply and demand. In capitalist societies, governments tend to intervene far less, and keep spending to a minimum.

In contrast, communism suggests that all wealth and property should be shared equally among the population, and all the means of production should be owned by the community.

Socialism, another term you will encounter, is a less extreme cousin of communism. It advocates for government to tax the rich more heavily, and to spend more readily on the poor, in order to redistribute wealth, with the aim of creating a more equitable society.

These definitions should be treated only as a jumping off point, since these terms are far more complex than these short definitions give them credit. There is also frequently a wide gulf between these ideas as theories, and how they pan out when implemented in real life.

2 If you are abrogating responsibilities, it basically means you’re evading or dodging responsibilities.

A dogma is a formal set of beliefs. So you might have communist dogma, capitalist dogma, socialist dogma, catholic dogma – and so on!

3 Laissez-faire is a French term and it means ‘to leave alone.’ It is often used by economists to describe how the capitalist system works: the government is encouraged to simply leave things alone, and let the free market determine how things pan out.

4 You may well know this already, but war between Britain and Germany broke out in July 1914 – this was of course World War One. You may well also know that the Titanic sank in April 1912.

5 Someone’s bona fides are their credentials.

To transgress is to go beyond or exceed what is permissible.

6 The word sardonic is very similar to sarcastic – a sardonic comment is usually a sarcastic one.

7 By an equivocal position, I mean an ambiguous/unclear position; a position that is somewhere between the two extremes.

8 If something is analogous to something else, it means that it is similar to that thing.

9 En route is a French phrase. To be en route somewhere means to be on the way somewhere.

Photos 1, 2 & 4 Copyright © Tim Green. Licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Photo 1: ‘Smoke Ring’

Photo 2: ‘JB Priestley’

Photo 4: ‘OM’

You can purchase a copy from any of these booksellers:

Alternatively, you can purchase and download an electronically delivered PDF directly from us here.

Quotes From Our Customers

My daughter found it really useful, so much so that her practice GCSE essay she recently handed in on the inspector calls gained her a grade 9. I also briefly showed it to once of the English teachers at the school where I work, her only comment was “this is fab, it’s really easy to understand and has some amazing advice that any of our students would find really helpful”.

I am a secondary English tutor and I often struggle to recommend study guides to students who are aiming for the very highest grades. Normally, they are too simplistic and do not encourage a sophisticated enough level of thought. This guide is great because of the way it shows students a thematic approach to writing an essay, which naturally helps students explore more insightful ideas about the play. It is fully linked to the AQA assessment objectives, and will really help those students who are naturally very able, but have not quite unlocked the right approach to get the top grades. The language is advanced, and it is not suitable for lower level students, but for those aiming for Grades 7 to 9 it is a really valuable resource.

An excellent GCSE revision aid - for both students and teachers. It really helps those wanting to achieve top grades to properly analyse the text fully and understand how to achieve those higher grades. As both a secondary teacher and parent of a year 11 student I would highly recommend as an essential guide to support gcse success.

Thought it was so good I went onto amazon and purchased Macbeth and Jekyll and Hyde versions too!!

I found this guide clear and very useful. I liked the layout with different essay structures and i also liked how clearly it explained each one. I found this book very helpful for preparing for my GCSE's and would really recommend it! thank you so much!

Fantastic purchase. The book is extremely helpful and is a great aid in studying An Inspector Calls. Would highly recommend it! I would go so far as to say, a sound knowledge of the text and this study guide is all a student needs to get the top top grades!

A brilliant guide according to my year 10 daughter. She said it provided good detail on how to write the essays and provided lots of examples on how to approach different essay questions. It helped her understand what to focus on and how to structure responses.

My year 10 son is finding this guide a lot of help. The thematic approach is a new thing to me and I like the idea of it and it will be helpful with other subjects too. The essay plans are going to be a great learning tool. So glad I found this book. Would highly recommend.

This guide offers students an alternative view to writing essays and a depth of material to really set them up with a solid foundation for their studies and exams. For those students who struggle to get started on 'how to' write a good essay, this guide gives excellent advice and examples. It helps to de-mystify the Assessment Objectives in an accessible way. An extremely helpful guide.

This guide has several essays, all of which are broken down and accompanied by sections of the mark scheme to explain why certain points have been included, and what you need to do to achieve the highest grades. It has points on historical context and the structure of the play, and inspires deep thought on the text.

The breakdown of the assessment objectives in the foreword [is] really helpful, and the overall structure of each essay makes it easy to follow and easy to understand where marks for each of the assessment objectives would be given.

I have a child studying this at GCSE and feel that the model essays will be really helpful in allowing him to think about all the different elements needed to write a good essay. I particularly enjoyed the useful hints on how to add historical context as this is easy to overlook.

My son’s GCSE curriculum includes An Inspector Calls as the coursework element. This Essay Writing Guide was therefore a perfect resource to aide him in constructing his coursework essay, in conjunction with feedback from his teacher. He is a maths whizz but finds English Literature far more challenging so having this handy guide to refer to and check that he’s on the right track has been invaluable. We highly recommend this guide to support your children/students in helping them achieve the highest possible marks.

Any questions or feedback? Need support? Want to purchase our resources on behalf of a school? Get in touch with our team at info@accoladetuition.com, and we shall endeavour to reply within 48 hours.

Visit us on Twitter to hear the latest Accolade Press news. Also: we'd love to hear about your learning journey. Use the hashtags #AccoladeGuides and #revisiongcse to spread the word.

To learn about our tuition services, please click here.

Cookies are important. Please click here to review our cookie policy.

We value the privacy of our users: you can read our privacy policy here.