ROMEO AND JULIET

An Essay Writing Guide for GCSE (9-1)

So you now know the play – but how do you structure your essay?

This clean & simple new guide from Accolade Press will walk you through how to plan and structure essay responses to questions on Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet. By working through seven mock questions, these detailed essay plans will show you how to go about building a theme based answer – while the accompanying notes will illustrate not only how to masterfully structure your response, but also how to ensure all AQA's Assessment Objectives are being satisfied.

R.P. Davis has a First Class degree in English Literature from UCL, and a Masters in Literature from Cambridge University. Aside from teaching GCSE English (which he's done for nearly a decade now), he has also written a string of bestselling thriller novels

Online shopping options:

Alternatively, you can purchase and download an electronically delivered PDF directly from us here.

SAMPLE FROM THE GUIDE

Foreword

In your GCSE English Literature exam, you will be presented with an extract from Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet and a question that asks you to offer both a close analysis of the extract plus a commentary of the play as a whole. Of course, there are many methods one might use to tackle this style of question. However, there is one particular technique which, due to its sophistication, most readily allows students to unlock the highest marks: namely, the thematic method.

To be clear, this study guide is not intended to walk you through the play scene-by-scene: there are many great guides out there that do just that. No, this guide, by sifting through a series of mock exam questions, will demonstrate how to organise a response thematically and thus write a stellar essay: a skill we believe no other study guide adequately covers!

I have encountered students who have structured their essays all sorts of ways: some by writing about the extract line by line, others by identifying various language techniques and giving each its own paragraph. The method I’m advocating, on the other hand, involves picking out three to four themes that will allow you to holistically answer the question: these three to four themes will become the three to four content paragraphs of your essay, cushioned between a brief introduction and conclusion. Ideally, these themes will follow from one to the next to create a flowing argument. Within each of these thematic paragraphs, you can then ensure you are jumping through the mark scheme’s hoops.

The Shakespearian equivalent of a selfie.

So to break things down further, each thematic paragraph will include various point-scoring components. In each paragraph, you will quote from the extract, offer analyses of these quotes, then discuss how the specific language techniques you have identified illustrate the theme you’re discussing. In each paragraph, you will also discuss how other parts of the play further illustrate the theme (or even complicate it). And in each, you will comment on the era in which the play was written and how that helps to understand the chosen theme.

Don’t worry if this all feels daunting. Throughout this guide, I will be illustrating in great detail – by means of examples – how to build an essay of this kind.

The beauty of the thematic approach is that, once you have your themes, you suddenly have a direction and a trajectory, and this makes essay writing a whole lot easier. However, it must also be noted that extracting themes in the first place is something students often find tricky. I have come across many candidates who understand the extract and the play inside out; but when they are presented with a question under exam conditions, and the pressure kicks in, they find it tough to break their response down into themes. The fact of the matter is: the process is a creative one and the best themes require a bit of imagination.

In this guide, I shall take seven different exam-style questions, coupled with extracts from the play, and put together a plan for each – a plan that illustrates in detail how we will be satisfying the mark scheme’s criteria. Please do keep in mind that, when operating under timed conditions, your plans will necessarily be less detailed than those that appear in this volume.

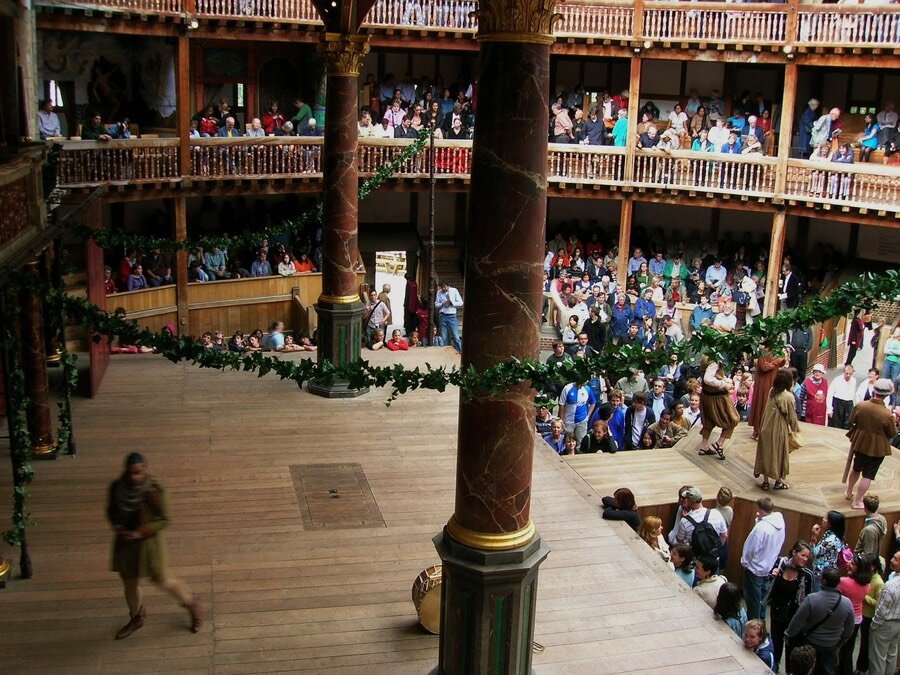

The Globe Theatre in London. It was built on the site of the original, which was burnt down in 1613.

Now, you might be asking whether three or four themes is best. The truth is, you should do whatever you feel most comfortable with: the examiner is looking for an original, creative answer, and not sitting there counting the themes. So if you think you are quick enough to cover four, then great. However, if you would rather do three to make sure you do each theme justice, that’s also fine. I sometimes suggest that my student pick four themes, but make the fourth one smaller – sort of like an afterthought, or an observation that turns things on their head. That way, if they feel they won’t have time to explore this fourth theme in its own right, they can always give it a quick mention in the conclusion instead.

* * *

Before I move forward in earnest, I believe it to be worthwhile to run through the four Assessment Objectives the exam board want you to cover in your response – if only to demonstrate how effective the thematic response can be. I would argue that the first Assessment Objective (AO1) – the one that wants candidates to ‘read, understand and respond to texts’ and which is worth 12 of the total 34 marks up for grabs – will be wholly satisfied by selecting strong themes, then fleshing them out with quotes. Indeed, when it comes to identifying the top-scoring candidates for AO1, the mark scheme explicitly tells examiners to look for a ‘critical, exploratory, conceptualised response’ that makes ‘judicious use of precise references’ – the word ‘concept’ is a synonym of theme, and ‘judicious references’ simply refers to quotes that appropriately support the theme you’ve chosen.

The second Assessment Objective (AO2) – which is also responsible for 12 marks – asks students to ‘analyse the language, form and structure used by a writer to create meanings and effects, using relevant subject terminology where appropriate.’ As noted, you will already be quoting from the play as you back up your themes, and it is a natural progression to then analyse the language techniques used. In fact, this is far more effective than simply observing language techniques (personification here, alliteration there), because by discussing how the language techniques relates to and shapes the theme, you will also be demonstrating how the writer ‘create[s] meanings and effects.’

Now, in my experience, language analysis is the most important element of AO2 – perhaps 8 of the 12 marks will go towards language analysis. You will also notice, however, that AO2 asks students to comment on ‘form and structure.’ Again, the thematic approach has your back – because though simply jamming in a point on form or structure will feel jarring, when you bring these points up while discussing a theme, as a means to further a thematic argument, you will again organically be discussing the way it ‘create[s] meanings and effects.’

The Globe Theatre’s interior.

AO3 requires you to ‘show understanding of the relationships between texts and the contexts in which they were written’ and is responsible for a more modest 6 marks in total. These are easy enough to weave into a thematic argument; indeed, the theme gives the student a chance to bring up context in a relevant and fitting way. After all, you don’t want it to look like you’ve just shoehorned a contextual factoid into the mix.

* * *

My hope is that this book, by demonstrating how to tease out themes from an extract, will help you feel more confident in doing so yourself. I believe it is also worth mentioning that the themes I have picked out are by no means definitive. Asked the very same question, someone else may pick out different themes, and write an answer that is just as good (if not better!). Obviously the exam is not likely to be fun – my memory of them is pretty much the exact opposite. But still, this is one of the very few chances that you will get at GCSE level to actually be creative. And to my mind at least, that was always more enjoyable – if enjoyable is the right word – than simply demonstrating that I had memorised loads of facts.

Essay Plan One

Read the following extract from Act 1 Scene 2 of Romeo and Juliet and then answer the question that follows.

At this point in the play, Paris is asking Capulet for Juliet’s hand in marriage.

PARIS

But now, my lord, what say you to my suit?

CAPULET

But saying o’er what I have said before:

My child is yet a stranger in the world;

She hath not seen the change of fourteen years,

Let two more summers wither in their pride,

Ere we may think her ripe to be a bride.

PARIS

Younger than she are happy mothers made.

CAPULET

And too soon marr’d are those so early made.

The earth hath swallow’d all my hopes but she,

She is the hopeful lady of my earth:

But woo her, gentle Paris, get her heart,

My will to her consent is but a part;

An she agree, within her scope of choice

Lies my consent and fair according voice.

Starting with this extract, explore the degree to which you think Shakespeare portrays Lord Capulet as a bad father.

Write about:

• how Shakespeare portrays Capulet in this extract.

• how Shakespeare portrays Capulet in the play as a whole.

Introduction

The introduction should be short and sweet, yet still pack a punch. I personally like to score an early context point (AO3) in the opening sentence. Then, in the second sentence, I like to hint at the themes I’m going to cover, so that the examiner feels as though they have their bearings and is thus ready to hand out AO1 marks.

In this instance, I score early AO3 marks by invoking another Shakespeare text that places Romeo and Juliet in context. After this, I keep things short and sweet, hinting at the ambivalent approach I am about to take.1

“Father-daughter relationships abound in Shakespeare: the other mid-1590s sister play to Romeo and Juliet – A Midsummer’s Night Dream – starts with a father, Egeus, threatening his daughter, Hermia, with unwanted wedlock. However, while Capulet puts on a similar performance, he also embodies a host of admirable qualities that complicate an audience's perception.”

Theme/Paragraph One: Capulet exhibits genuine concern for his daughter’s wellbeing: in this extract, he is particularly concerned about his daughter marrying too young. However, this is undercut later in the play by his heavy-handed attempt at discipline.

As suitors go, Paris is hardly presented as a menacing presence: he politely asks Capulet for Juliet’s hand: ‘what say you of my suit?’ Nevertheless, Capulet quickly makes known his worries about Juliet’s extreme youth (‘not seen the change of fourteen years’), and exhibits concern that an early marriage could be detrimental: ‘Too soon marr’d are those early made.’ The alliteration of ‘marr’d’ and ‘made’ adds emphasis to Capulet’s point by powerfully linking these words: those who get made in marriage too soon end up marred.2 Capulet seems genuinely concerned for his daughter’s wellbeing and the implication of her tender age. [AO1 for advancing the argument with a judiciously selected quote; AO2 for the close analysis of the language].

However, although Capulet is presented as a caring father towards Juliet here, elsewhere he is presented as the polar opposite. In Act 3 Scene 5, Capulet, in the wake of Juliet’s refusal to marry Paris, threatens his daughter with violence (‘my fingers itch’) and brutally objectifies her: ‘You be mine, I’ll give you to my friend.’

Theme/Paragraph Two: Capulet in this extract is portrayed as emotionally frail, and arguably this frailty leads to an anxiety-driven, rash decision.

Capulet in this extract is oddly mercurial and rash in his decision making: at first, he is against Paris courting his daughter; yet, in the space of a few lines, he changes his mind: ‘woo her gentle Paris.’3

Although it might be argued that this vacillation should be attributed to Capulet’s deep concern for his daughter – an instinct to marry her to someone who can provide for her – on closer inspection, this is only half the story. Capulet lets slip that he has lost other offspring: he claims that ‘The earth hath swallow’d all my hopes but she’ – the image of a personified earth eating his hopes communicating the fact other offspring have been buried, while the elision in ‘swallow’d’ has the missing ‘e’ mirror this loss.4 As a result of this emotional wound, Capulet goes against his own better judgement to ‘let two more summers wither’ and makes a rash volte-face.5 His concern for his daughter, therefore, is not only counterbalanced by a fierce temper, but also compromised by an emotional wound that muddles Capulet’s decision making. [AO1 for advancing the argument with a judiciously selected quote; AO2 for the close analysis of the language].

However, later in the play, one sees that Capulet’s frailty lends him greater emotional intelligence as a father: after Juliet feigns her death in Act 4, Capulet mourns her death with moving poetry: ‘Death lies on her like an untimely frost / Upon the sweetest flower.’ That this elegy comes right at the close of Act 4 lends it extra structural emphasis, since the natural pause between acts forces the audience to linger on the words.6 [AO2 for observing how structure shapes meaning].

Theme/Paragraph Three. Capulet is a good father insofar as he sets a positive example in the way he interacts with the wider world.

In this passage, Capulet comes across as a positive role model in the community. He deals with Paris in a calm, respectful manner – even though Paris is pursuing his young daughter. Even if one disagrees with his final response, he does show patience with Paris. Indeed, Capulet does not monologue at Paris; rather, there is a respectful back and forth, and Capulet gives Paris space to speak. This is exemplified by Paris’s line – ‘younger than she are happy mothers made’ – midway through the extract: Shakespeare, by interpolating this line amid Capulet’s words, uses form to relay a sense of respectful dialogue. [AO2 for observing how form shapes meaning].

Elsewhere in the play: At Capulet’s party, Capulet attempts to keep the peace when Tybalt is trying to escalate tensions with the Montague gatecrashers. However, whereas Capulet cast himself as a respectable role model in this scene, at other points in the play he falls well short: the audience’s very first introduction to Capulet, prior to this extract, sees him seeming to lust for violence: ‘Give me my long sword, ho!’ – Shakespeare’s structural decision to place this line in the play’s opening scene lending it extra emphasis. [AO2 for observing how structure shapes meaning].

Conclusion

I have a smaller theme tucked up my sleeve; however, given the length of the previous themes, it feels wisest to integrate it into the conclusion. I wish to point out that Capulet exhibits a flexibility that boosts our estimation of his fathering abilities...

“Capulet – like the play in which he appears – embodies powerful contrasts: he is a positive role model to Juliet, yet a provocateur; an empathetic father, but callous.7 This extract exemplifies Shakespeare’s flair for ambiguity. Although one might argue (as above) that Capulet's volte-face ought to be considered a flaw, it could equally be considered a virtue: he has an admirable capacity for flexibility, which allows him to hew to Juliet’s choices in a way that empowers her: ‘Within her scope of choice / Lies my consent and fair according voice.’ The audience is left feeling as if Capulet is ‘a stranger in this world’ – an individual beyond our ability to definitively decipher.”

1 To be ambivalent is to have mixed feelings about something or someone.

2 If something has been marred, it has been damaged or disfigured.

3 If someone is mercurial, it means their mood or state of mind is frequently subject to change.

4 Elision is when you remove a syllable or a sound from a word, and is usually signified by an apostrophe replacing the missing syllable. We use elision all the time in present-day English – for example, ‘let’s’ and ‘I’m’.

5 A volte-face is when someone takes the polar opposite view to the one they previously held.

6 An elegy is a lyric or poem that involves deep contemplation, and is most frequently seen during the commemoration of a death.

7 A provocateur is someone who intentionally acts in such a way as to provoke strong emotions in others.

Proceeding chapters….

Essay Plan Two: explain how Shakespeare presents Romeo’s feelings towards Juliet.

Essay Plan Three: explain how far you think Shakespeare presents the Friar as a positive influence.

Essay Plan Four: explain how far you think Shakespeare presents Mercutio as a heroic character.

Essay Plan Five: explain how Shakespeare presents the idea of justice in Romeo and Juliet.

Essay Plan Six: discuss to what extent the Nurse is portrayed as a maternal figure in the play.

Essay Plan Seven: explain how Shakespeare portrays grief in Romeo and Juliet.

Alternatively, you can purchase and download an electronically delivered PDF directly from us here.

CUSTOMER REVIEWS

I love this book as in how specific it is in terms of delivering how students should study the extracts of Romeo and Juliet. I am a tutor and I believe this is a possible guidance to how to study literature and the answering techniques to literature exams. Not only is the mindset applicable to questions related to Romeo and Juliet, but also to literature in GCSE in general. This is a book that students would want to read because the language is not hard either, and it patiently guides you through - highly recommended to GCSE students (and tutors perhaps!)

This is a really useful revision guide in a great format. Focussing on the structure of planning and writing essays in the way that examiners are looking for is so useful for GCSE students. This book shows that it's not just about memorising content, but understanding key themes, events and quotations to gain higher marks. I would love to see a guide like this for more texts!

I found this text really useful from a parent's point of view, as it helped me understand what the exam questions are looking for, and will enable me to help my child better. It gives us a starting point for discussion for any exam question, not just those specific ones covered. Really clear structure. Would be great to see this format for other Shakespeare plays.

This is an extremely helpful guide to help students formulate and structure GCSE essay questions. Using a varied range of sample questions on the text it unpicks potential answers paragraph by paragraph and really helps students learn how to incorporate themes and gain those extra marks from the very start of the question. My daughter will find it invaluable in her GCSE revision.

Excellent guide for students going for the highest grades.

This is not a basic guide to R&J but rather an explanation as to how to structure essays thematically so as to achieve the highest grades (the marking structure is explained). The book therefore sets out seven detailed essays plans relating to key passages in the text. On a basic level this would help any student think intelligently about characters and themes eg Shakespeare’s portrayal of the friar, the idea of justice etc, but in a higher level it suggests a structure help the most able students order their thoughts and think about themes and how to present them.

As someone who studied this text for GCSE in 1994, I wish this was around then. My daughter struggled with my old revision guide but says this is laid out in such a way that it is clear to follow. It unpicks what the questions actually want as answers by liking at the questions in detail but simply enough to understand.

It was very easy to read and understand and stimulated further thoughts that my daughter agreed she hadn’t necessarily considered. She found it very comprehensive and has since used it when writing further essays. She has used some the the techniques suggested by the study guide to back up advice given by her teacher, which has definitely helped her gain higher marks, and made it a lot less stressful for her and us! As a parent it has helped me understand what information is expected from an exam perspective. Great guide would highly recommend.

My daughter got the guide to help aide with her studies.

She has found this particularly useful and would recommend this to all students taking their GCSEs.

It has helped retiterate points she has learned and helped with formation of essays, helping her put extra content in the writing.

A review from my son: This book is perfect for GCSE English students. It is easy to read it is pitched at just the right level for students hoping to get a high grade. It explains and demonstrates perfectly how to organise and write a Romeo and Juliet essay. It takes you through a good choice of possible exam questions and it emphasises how important the themes are. It shows you how to analyse themes and quotes from all parts of the play as well as showing you how to structure a response to the different questions and how give a much more in depth answer so you can get extra marks and a higher grade. I am now much more confident going into the exam!

As a parent, this is a really useful guide. It now gives me a much better idea of how I should be encouraging my son to prepare for his exams and make the best use of his revision time.

The essays in the book cover the main topics and typical questions that students may encounter in their exams. It clearly explains the marking criteria, so that students can fully understand how to bring in the different aspects into their own writing. The thematic approach gives them new ideas of how to approach the question and is helping them with their essay planning overall.

Any questions or feedback? Need support? Want to purchase our resources on behalf of a school? Get in touch with our team at info@accoladetuition.com, and we shall endeavour to reply within 48 hours.

Visit us on Twitter to hear the latest Accolade Press news. Also: we'd love to hear about your learning journey. Use the hashtags #AccoladeGuides and #revisiongcse to spread the word.

To learn about our tuition services, please click here.

Cookies are important. Please click here to review our cookie policy.

We value the privacy of our users: you can read our privacy policy here.